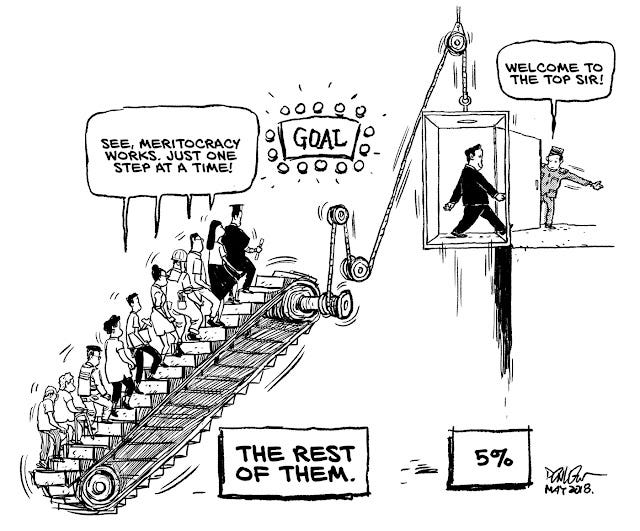

THIS IS WHAT MERITOCRACY LOOKS LIKE: AN ECONOMIC ANALYSIS

MY LIVED EXPERIENCES

This analysis of our education system draws from Dawn Fung’s book “Homeschooling in Singapore: An Education”.

(Dawn’s book can be bought here: https://www.wordimagesg.com/product-page/homeschooling-in-singapore-an-education),

Recently, the Singapore Ministry of Education and China Ministry of Education signed two Action Plans for Educational Technology and University Cooperation* – educational cooperation which showcases Singapore’s standing as one of the top places in the world to receive an education. The Primary School Leaving Education results have also been just released; the first step on a rung that is formal, compulsory schooling for many young Singaporeans.

Singapore’s education narrative is crafted along notions of meritocracy; that is, that one attains success through merit – hard work and effort put by children who go through our educational system will definitively pay off. This is concretized through state narratives, which highlight processions of scholars and outstanding individuals who achieved social mobility for themselves and their families by working hard. However, this neglects those who fall between the cracks; individuals like myself who fail to become scholars due to an inherent lack of privilege and a certain level of pre-existing inequality.

Nonetheless, I still consider myself blessed for I possess the academic ability and literary knowhow to write this essay.

For context, because of monetary constraints, I am one of the 3% who has never had tuition, save for a 2 month stint in Mathematics when I was 14. Despite a low-middle class family income for years, which was disrupted by my Father's mental health episodes, I am blessed to have made it to NUS (Economics and Philosophy) and NTU (Sociology) both.

THE HISTORY OF EDUCATION IN SINGAPORE

The history of education is a rich one, which Dawn's book details. Singapore has clearly drawn upon a mix of Western and Chinese traditions which inform our educational structures. Vocational institutions are the modern-day equivalent of young individuals joining guilds, while Confucianistic standards inform the necessity of examinations in Singapore. These self-same standards were where the beginnings of meritocracy originated, with the promise of social mobility and public titles awarded for individuals who successfully memorised canonical texts such as The Book of Rites, and the Analects.

Conversely, the concept of mass schooling originated from Great Britain and the Industrial Revolution, where the plight of the poor, the pursuit of schooling as a social movement, the working class’s desire for education and advocacy for compulsory schooling caused the proliferation of educational institutes to develop alongside the speed of production in factories. This is again, reproduced in Singapore (and not necessarily in a bad way) through the multiplicity of schools in every district.

THE IMPORTANCE OF STATE-RUN EDUCATION: FACILITATING THE SOCIALIZATION PROCESS FOR CITIZENS WHILE MAXIMIZING HUMAN CAPITAL

The opening section of Dawn’s book emphasizes the absence of children's rights in world education history, something overlooked in mass and compulsory schooling movements until recently. Mainstream schools, which cater to the masses under a state direction, do not prioritize the freedom and autonomy to choose the configuration of educational pedagogy that best fits the learner. She draws upon the history of education in multiple countries to illustrate this, determining a bifurcation between mass schooling and compulsory schooling, the latter which she states kills the incentivising factor for parents.

She contrasts the history of education in multiple countries to create a comprehensive overview; from the British Empire and its entrenchment in social class divides - where educational privileges were not as keenly shared with the working classes by the ruling elites- to the German state of Prussia, where education was akin to conscription, and religion institutionalized as constitutive of the curricula (Protestant Christianity, in this case). Both countries represent bifurcating views with respect to education, yet each reflect how education policies are aligned to national interests, and not the interests of the learners.

Singapore’s Meritocratic System as Paralleling that of Otto Von Bismarck’s Contribution to Prussia

Some background information is thus necessitated here. While Singapore’s meritocratic education system was primarily based on Britain and the U.S, a multiplicity of global factors shaped Singapore’s education system as well.

In particular, Singapore’s meritocratic education system shares striking parallels with the Prussian model championed during Bismarck’s** era, particularly in Prussia’s centralized governance and emphasis on aligning education with national goals.

Otto von Bismarck, the "Iron Chancellor," was renowned for his role in unifying Germany (1871) and his statesmanship as Chancellor of the German Empire (1871–1890). His influence extended to the Prussian education model, which became a tool for nation-building and fostering loyalty to the state. Under his leadership, the education system emphasized discipline, obedience, and civic duty, aligning with Bismarck’s vision of a cohesive German society. Prussia had already pioneered compulsory education in the 18th century, but during Bismarck’s era, it became further centralized, ensuring that curricula, teacher training, and administration served the state's goals. Education also played a critical role in preparing citizens for an industrialized economy, military service, and civil administration.

A significant aspect of Bismarck’s policies concerning education was his Kulturkampf ("Culture Struggle") from 1871 to 1878, which aimed to reduce the Catholic Church’s influence in public life, including education. Bismarck believed that the Church’s control over schools undermined state authority and national unity. He passed laws transferring the administration of schools to the state, established secular teacher training institutions, and required all schools to operate under state supervision. While the Kulturkampf initially intensified tensions, especially with Catholic communities, its long-term impact strengthened the secular, state-controlled nature of the Prussian education system.

Bismarck’s reforms and policies laid the groundwork for a highly efficient and centralized education system that influenced modern public education worldwide. However, his focus on conformity and state service often stifled creativity and critical thinking. Despite these limitations, the Prussian model became a blueprint for many countries seeking to establish compulsory education systems, marking Bismarck’s enduring legacy in shaping education.

An evaluation of Singapore’s education system would thus necessitate comparison to Bismarck’s reforms, as both systems leverage education as a critical tool for fostering societal cohesion, ensuring economic productivity, and addressing the specific needs of their respective states. However, their divergences reveal the evolution of educational philosophies, reflecting shifts in societal values and priorities.

In the Prussian model, the state maintained strict control over curricula, teacher training, and school administration to ensure uniformity across the newly unified German Empire. Similarly, Singapore’s Ministry of Education (MOE) oversees and standardizes key aspects of education, from the design of national curricula to the execution of policies. The standardization practiced by both countries ensures consistency and alignment with national objectives. In the present day, that includes the fostering of bilingualism, national harmony and civic loyalty*** in Singapore; the last being something promoted in Prussia as well in the past.

Both systems also utilized education as a means to instill shared values among citizens. For Prussia, this meant cultivating discipline, obedience, and nationalism in students, preparing them to serve the state’s military and bureaucratic needs. Singapore, while significantly less authoritarian in nature, similarly emphasizes national unity through shared narratives of resilience, multiculturalism, and meritocracy. Students are encouraged to view themselves as contributors to Singapore’s economic success and global competitiveness.

Another point of convergence is the use of educational streaming to align education with workforce needs. In Prussia, students were sorted into vocational or academic tracks based on their aptitudes, ensuring an efficient pipeline of skilled workers, military personnel, and civil servants. Singapore adopts a comparable approach through its meritocratic streaming system, where students are placed into pathways such as Express, Normal (Academic), or Normal (Technical), and later specialized tracks in higher education, such as STEM, arts, or vocational training. This ensures that students are trained according to their strengths and the needs of the economy.

In Singapore, with narratives of nation-building emphasizing how we are our own natural resources, with the government spending 17.2% of GDP on education**, every human is seen as human capital, a term that is coined by American economist Theodore William Schultz, as reproduced in Dawn’s book:

“Since education becomes a part of the person receiving it, I shall refer to it as human capital. Since it becomes an integral part of a person, it cannot be bought or sold or treated property under our institutions. Nevertheless, it is a form of capital if it renders a productive service of value to the economy.”

A BRIEF ECONOMIC INTERLUDE

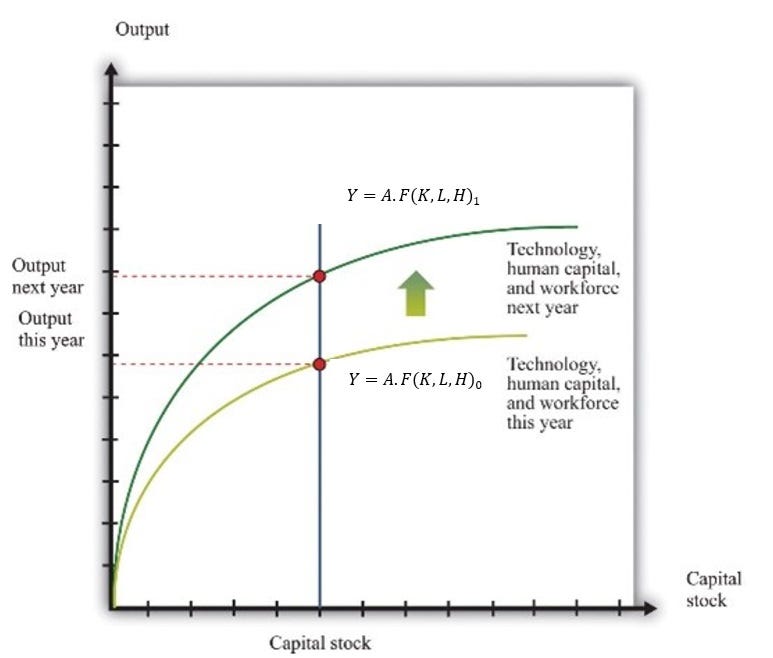

Some basic Keynesian economics needs to be explained here. Human capital refers to the knowledge, skills, education, and health of the workforce. This is reflected in the aggregate production function - a.k.a the curved lines on the graph.

The function of the graph is as follows: Y=A . F(K, L, H), where

Y is total output (GDP),

A is total factor productivity (TFP, reflecting technology and efficiency),

K is physical capital,

L is labor,

H is human capital.

An increase in H (human capital) enhances the productivity of labour (L), making each worker more capable of producing higher output. This improvement shifts the production function upwards (as illustrated), which is the aim of our government’s education policies.

The abovementioned can also be further illustrated as follows:

The Horizontal axis represents inputs (labor, capital, or effective units of labor accounting for human capital improvements),

The Vertical Axis: Output (GDP) – Economic growth, which is the aim of all governments, in sustaining our economy.

Improvements in human capital shift the curve upward because, for any given level of physical capital and raw labor, the economy can now produce more output. This reflects the enhanced capability of the workforce due to better skills and knowledge. Conversely, a movement along the production function is a consequence of the government increasing the amount of labour (L) or human capital (H), which is limited by our falling birth rates and limited land space (as well as migratory policies, which I will delve into at a different time)

One of the key ways of improving human capital is therefore (rather intuitively) Education, which is extremely beneficial to our economy due to the following effects:

Higher Marginal Productivity of Labor: Workers with more education, better training, and improved health are more productive. This raises the marginal productivity of labor and increases total output.

Skill-Biased Technological Progress: Improvements in human capital enable workers to use advanced technologies effectively, amplifying the effects of technological progress (A).

Economic Growth: In growth models (like those of Solow or endogenous growth theories), human capital accumulation contributes to sustained economic growth by increasing the efficiency and innovation capacity of the economy.

Considering our pragmatic governance which follows economic rationality, subjects and courses taught within Singapore’s education system are thus meant to improve the productivity and quality of labour, considering our primary reliance on human capital for economic growth – apart from other variables that improve our GDP, such as FDI (Foreign Direct Investments).

This is thus a problem when certain skillsets are prioritized over others, generating inequalites of privilege between students who may be inherently talented in different skills not valued in the existing education system, such as Arts and Crafts. This is further exacerbated considering the main critique of meritocracy – that the level playing field is not the same for all students – due to unequal salaries of households, availability of parental figures, and within each child, differing talents, proclivities, and behavioural tendencies. However, programs like SkillsFuture and pathways for polytechnic students to enter universities exemplify Singapore’s efforts to maintain upward mobility. The government also actively seeks to address these inequalities through bursaries, financial aid, and educational outreach programs.

Returning back to the comparison between Prussia and Singapore, the biggest difference between both systems is that of the philosophical underpinnings of the two disparate states. The Prussian model was heavily focused on creating obedient, state-serving citizens, with education functioning as a mechanism for social order and control. It emphasized rote memorization and conformity, leaving little room for creativity or critical thinking.

In contrast, Singapore’s education system, while disciplined, is forward-looking, prioritizing innovation and adaptability alongside academic excellence. Initiatives like the Applied Learning Programme (ALP) and emphasis on STEM education reflect Singapore’s recognition of the need for critical thinking and creativity in a globalized world. This is best exemplified through MOE’s launching of the “Transforming Education through Technology” Masterplan 2030 or “EdTech Masterplan 2030” for short, which outlines how schools can better leverage technology to enhance teaching and learning. This addresses the opportunities and challenges of the post-COVID landscape, where technology has become a critical enabler of learning.

Lastly, one must not forget that both systems are products of their historical and political contexts. The Prussian model was instrumental in consolidating a fragmented Germany, laying the foundation for a disciplined and loyal citizenry to support state-building efforts. Singapore’s system, by contrast, is designed to sustain its small, resource-scarce nation’s relevance in the global economy. The Prussian model prioritized state authority over the individual, while Singapore’s system seeks to balance state interests with individual aspirations, encouraging students to achieve their personal best while contributing to national development.

Education as a Privilege – Elitism and Eugenics

Returning back to Dawn’s book, she also provides a comprehensive analysis and history of the PSLE (Primary School Leaving Examination). She details that Lee Kuan Yew’s conceptualization of Singapore’s education system was based on theoretical frameworks from Cyril Burt’s child science; that intelligence was innate and not environmentally influenced. LKY also drew inspiration from Darwin’s cousin, Francis Galton, who is the founder of eugenics. According to Galton, it was possible to select people and breed them according to desirable hereditary traits. The most intelligent and innovative members of society were to be found at the top of society, and not the bottom.

This has its roots in British colonialism, where the wars that the British were involved in depleted the “good stock” of the aristocracy. Physical replenishment was not found from the lower orders and not from other distinct races – especially those whose outward appearances supposedly justified their oppression and suppression by the colonialists. This is in line with race theory, which elucidates that the category of races was constructed for the benefits of the colonial conquerors. These have since been disproved.

Dawn articulates that while the PSLE is meant to be a labour sorting mechanism; focused on creating the ideal manpower for Singapore’s workforce, intelligence is too complex to be behaviourist or solely genetics based – being influenced by too many factors such as external socio-economic factors (e.g social and health outcomes), and some genetics, e.g cognitive function and personality traits pertaining to persistence and self-discipline; things that cannot be sorted so easily. She goes further to state that the PSLE marks the beginning of elitism, where students are sorted and demarcated by grade into elite versus non-elite schools, streams, and categories, which is problematic, as education in Singapore is now defined by placement, and not lifelong, self-directed learning.

The perpetuation of elitism is an underlying social issue caused by brand-name institutions within our education system (where intellectual competence through high grades serve as barriers to entry to said schools, through specialized streaming). This results in a stratified hierarchy, where high achievers are funneled into prestigious schools, scholarships, and leadership programs, while others are assigned to less celebrated pathways. This differentiation, while ostensibly merit-based, fosters elitism as those who succeed within the system gain disproportionate access to opportunities, resources, and networks that further entrench their advantages.

Over time, the clustering of high performers into elite institutions creates a self-perpetuating cycle, where the socio-economic backgrounds of students increasingly influence access to these opportunities. Families with greater resources invest heavily in private tuition and enrichment programs to secure a competitive edge, further widening the gap between high and average performers. While this model optimizes the allocation of talent to key industries and leadership roles, it also reinforces divisions within society, as success becomes concentrated among a privileged subset, making elitism a structural byproduct of the system’s drive to maximize human capital, which is a problem.

This is where I disagree with Dawn, despite drawing examples from Dawn’s book. We are actually very fortunate to be born in Singapore, considering how education used to be a privilege. In recent times, education is constitutive of international policy, being part of the UN’s SDG (Sustainable Development Goals) for all nations to adopt as part of a new UN program – the “2030 Agenda”. These encapsulate legally non-binding global policy norms agreed upon by governments across the world. As Singapore aims to maintain her competitiveness in the global economy, it makes economic sense for the government to maximize human capital (its citizens) through the education system - justified through the aggregate production function, which I have explained earlier. I argue that the stratified hierarchy and resulting elitism is but a byproduct of this.

Today, there are multiple pathways now for all throughout the education system – from primary school to university, to be part of this self-same elite.

Merit-based scholarships and awards (of varying tiers) are now increasingly available to students from different streams, as the government is adopting a more holistic approach to education, best exemplified through the Lee Kuan Yew Gold Medal, that is awarded across institutions, from ITE to NUS/NTU/SMU. Moreover, this begs the following questions: What are the parameters delineating a member of the elite from the common, everyday Singaporean? Are these clear and defined? Or are they grey areas that encapsulate a myriad of spheres - social capital, economic capital, intellectual capital?

Thus, I argue that our government is actually doing its best to foster true meritocracy.

WHY HOMESCHOOLING IS NECESSARY IN SINGAPORE: ADDRESSING MARKET FAILURE IN EDUCATION

The meritocratic education system in Singapore, lauded for its high academic standards and global competitiveness, is nevertheless not without its economic shortcomings. This is where the theory of market failure comes in, which will be expounded in the latter half of this essay. As an inherently competitive framework, meritocracy often leads to inequities and inefficiencies, which homeschooling, as discussed in Homeschooling in Singapore: An Education, emerges as a vital alternative to address these gaps. This is because Homeschooling offers a more personalized and holistic approach to learning.

Market Failure in the Meritocratic Education System

Market failure in Singapore’s education system manifests in two key ways: inequity of opportunity and negative externalities. While meritocracy ostensibly rewards talent and effort, it often perpetuates socio-economic disparities. To expound upon the earlier mentioning of inequalities of privilege, families with greater financial resources can afford tuition, enrichment classes, and other means of academic advantage, creating an uneven playing field. This results in what economists term “market distortion,” where access to resources, rather than innate ability or effort, often determines outcomes. This perpetuates existing social inequality, as families with lesser financial resources produce children (and later adults), who do not have as many financial resources as the more privileged, due to worser educational, and income outcomes. This results in an never-ending cycle, as families struggle to break free of generational poverty.

Another instance of market failure is that of negative externalities evident in the high-pressure environment of Singapore’s education system. These refer to unintended adverse effects that spill over into society. The high-stakes nature of the system fosters a culture of intense competition, often resulting in heightened stress, anxiety, and even mental health issues among students, which has ossified as studies have shown that 33% of youth in Singapore experience severe, or very severe symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress****.

These effects are not confined to individuals but ripple across families and society at large, imposing hidden costs. For instance, the emphasis on academic achievement has led to the proliferation of private tuition and enrichment classes, contributing to a "tuition arms race" that amplifies disparities between socio-economic groups, as these classes tend to increase prices of their services in accordance with the success of their students. This phenomenon exacerbates inequality, as wealthier families can invest more in such services, creating an uneven playing field and perpetuating the very gaps that meritocracy seeks to bridge.

Furthermore, the narrow focus on academic credentials and test performance marginalizes other critical aspects of holistic development, such as creativity, social skills, and emotional intelligence. As a result, the workforce may lack the diversity of skills needed for a rapidly evolving global economy, imposing long-term costs on societal resilience and innovation. These systemic pressures highlight a market failure where the education system, driven by meritocratic principles, prioritizes individual advancement at the expense of broader societal well-being and equity. Dawn highlights these issues (minus the economic slant of this review), pointing out how the rigid structures of conventional schooling may not serve all children equally or effectively.

(image taken from tutor2u.com)

Homeschooling as a Corrective Mechanism

Homeschooling thus provides a viable alternative to these systemic shortcomings, offering families the flexibility to tailor education to their children’s unique needs, interests, and strengths. Dawn argues that homeschooling allows parents to step outside the constraints of one-size-fits-all education, addressing the inequities and inefficiencies of the meritocratic system. In her book, she emphasizes that homeschooling fosters a deeper sense of ownership over learning, encouraging children to explore their passions and develop critical thinking skills in a low-pressure environment.

By shifting the focus from competition to curiosity, homeschooling mitigates the negative externalities of Singapore’s education system. Children are free to learn at their own pace, engage with topics that resonate with them, and develop life skills that are often sidelined in traditional schools. This aligns with the principle of allocative efficiency, where resources (in this case, educational time and effort) are directed towards the areas where they yield the highest value for the individual.

Homeschooling and Social Equity

Homeschooling also offers a pathway to greater social equity by providing parents with the opportunity to fill gaps left by the system, particularly for children with special needs (neurodivergent children) or unconventional learning styles.

For children from disadvantaged backgrounds or those who face barriers in traditional schooling—such as learning disabilities, mental health challenges, or social stigma—homeschooling can create an environment where they thrive without the pressure of standardized testing and rigid academic streams. Dawn highlights how homeschooling empowers parents to focus on their children’s strengths and weaknesses, fostering self-confidence and individualized success in ways that the traditional system cannot accommodate.

Homeschooling also mitigates the existing over-reliance on credentials promulgated by Singapore’s meritocratic system by emphasizing lifelong learning, soft skills, and critical thinking—qualities that better prepare children for diverse career paths and economic participation. By fostering supportive, inclusive networks of homeschooling families, this approach also cultivates communities that share resources and expertise, bridging gaps between socio-economic groups. This is further underscored by Dawn’s advocacy, that these homeschooling communities create support networks that allow parents and children to thrive outside the confines of traditional schooling. This serves to foster both academic success and emotional well-being. Thus, homeschooling provides a practical and adaptable means to address inequities within Singapore’s high-stakes, merit-driven educational system.

A Complement, Not a Replacement

While homeschooling is not a panacea, it serves as an essential complement to Singapore’s meritocratic education system, addressing the market failures that disproportionately affect certain students. Dawn’s vision for homeschooling is not about rejecting conventional schooling but expanding the options available to families, ensuring that every child has access to an education that aligns with their needs and potential.

As Singapore strives to remain a global leader in education, acknowledging and supporting homeschooling as a legitimate and valuable alternative will enable the nation to move closer to its goal of inclusive, equitable, and meaningful learning for all. I end this analysis with the following quote:

“Education is the kindling of a flame, not the filling of a vessel.”

― Socrates

*The People’s Republic of China, Ministry of Education. Wang Guangyan visits Singapore, signs educational cooperation action plans. Press Releases, Nov 14, 2024.

**Blackbourn, D. (1977). The Kulturkampf and the limitations of power in Bismarck's Germany. The Journal of Ecclesiastical History, 28(3), 303–325. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022046900053602

***National Library Board Singapore. Values Education in Singapore. Singapore Infopedia. Retrieved 25 Nov, 2024.

****Goh, Timothy, and Felicia Choo. Singapore is No.13 globally in human capital study, beating Japan and the U.S. The Straits Times, Sep 25, 2018.

*****Teo, Joyce. Depression, anxiety, stress: 1 in 3 youth in S’pore reported very poor mental health, says IMH survey. The Straits Times, Sep 19, 2024.